[The featured image was AI-generated by ABSW on Canva]

The “Noise in Neuroscience” project for responsible sex and gender neuroscience research reporting, supported by the ABSW, has now published its guidelines in Nature Communications. Led by neuroscientist Gina Rippon, professor of cognitive neuroimaging at the Aston Brain Centre, the guidelines aim to improve coverage of sex and gender.

This is important because these are hot topics for the media, political actors and researchers. “[It] is worth stressing that, perhaps because of such extensive real-life relevance, it is important that any ambiguities or over-statements are avoided at source”, warns Rippon and the other authors of the Comment published in Nature Communications.

Rippon's team has voiced its concern over the potential life-long harm caused by misleading claims of sex/gender differences in the brain, and the wider problems these might cause for the reputation of the science community.

In an effort to take action and drive change, Rippon, Katy Losse and Simon White launched the “Noise in Neuroscience” project in September 2021. This resulted in a set of good practice guidelines, developed following workshops, public events, and an online survey, and with the support of the Royal Statistical Society and the Association of British Science Writers.

At the heart of ABSW’s involvement in the project is Board member Angela Saini, who took the metaphorical lid off and delved deeper during the dedicated discussion event hosted in London in 2022 (see playback here or above). Being at the forefront of such hard-hitting and controversial widespread research allows ABSW to improve its members' knowledge.

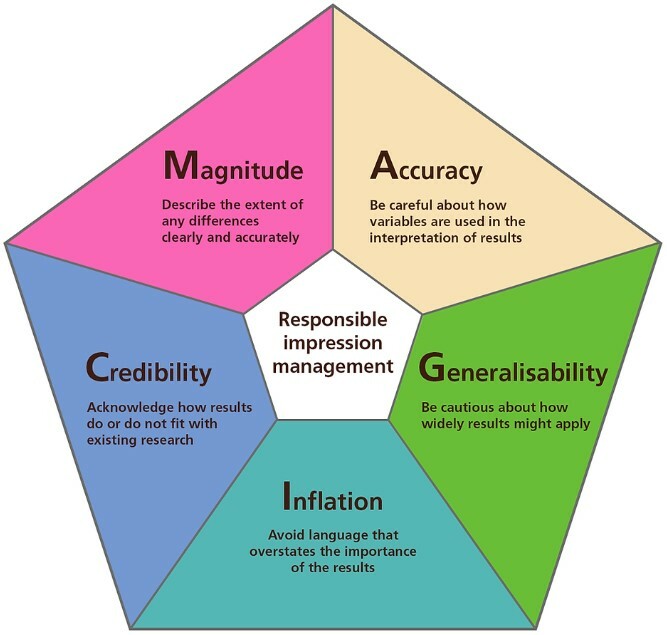

The ultimate aim of the project “Noise in Neuroscience”, as described by Rippon, is to “improve the way in which research into sex differences in the brain is communicated” by addressing some of the common pitfalls. The guidelines are designed to give a firm and objective foundation on which to base communication principles and challenge damaging claims. The MAGIC tool comprises five established factors to debunk the myths surrounding this area of research, whilst importantly allowing authors and editors to maintain their autonomy.

Fig. 1 - The five factors to be considered to prevent misleading and damaging claims from reaching the public domain. (Source: https://www.noiseinneuroscience.com/call-for-evidence)

Sex/gender and neuroscience research has the potential to impact everyone, serving as a platform for promoting equality, inclusion and diversity. However, mishandled reports can fuel stereotyping and attitudes across many fields, such as parenting, teaching and management, and can influence perceived opportunities and misguided self-beliefs. Where publication rates and impact are deemed a measure of success there is a need to strike a balance between generating exposure and accuracy, a challenge often faced by authors and journalists.

It seems the existing safeguards such as the longstanding peer review process are not driving the necessary change. So, who is responsible for impression management – the presentation of ideas to the public or those without specific scientific knowledge or understanding? The short answer is – everyone. Journalists, editors, peer reviewers, as well as researchers. They all have the responsibility to help the reader explore and understand the social, ethical, and political implications of research findings by reporting in a fair and balanced manner.

All forms of writing and communication, whether through podcasts, TV or radio, are the physical manifestation of the writer’s thoughts which may be biased by their ideology. Cognitive biases may not always be the result of purposeful manipulation or misinformation. Being unaware of your own biases subconsciously creeping into work and influencing outcomes makes you only human.

Here are some bitesize tips to go along with the MAGIC guidelines:

1. Narrative is a main issue; language is at its base an art, so extra caution and awareness of how words and definitions are used is recommended. More thoughtful narrative and emphasis on data, using colourful figures and metaphors etc., without relying on hype and hyperbole which distort empirical sex differences, can help get across technicalities whilst keeping readers engaged but, most importantly, still allow for maximal accuracy.

2. Using an impartial friend as a peer reviewer could give insight into how the general public/untrained eye may perceive ideas.

3. Asking when and why to include sex and/or gender as a variable. Is it appropriate for the outcome or to function as a gap-fill approach whereby sex differences are exploited in the absence of any other meaningful findings?

Going forward, the question remains: how to increase the uptake of rules and criteria by training and upskilling, losing the stigma of censorship, the antithesis of this movement. Outlining a need for critical thinking and scepticism concerning reported sex/gender differences by fundamentally assessing the narrative rather than indoctrination at face value. Essentially, are claims justified by what is stated?

Alternatively, should we be asking about sex/gender similarities in the brain rather than differences? Reframing the question removes the loaded weight and connotation that such differences are innate with extra steps needed to disprove such beliefs. In the wider context such implied suggestion curtails consideration of alternative conclusions for differences which can be observed between members of the same sex which remain overshadowed in research.