READ.

Newspapers, magazines, websites. Watch science TV programmes, listen to science podcasts and videos and other science media. Particularly as you discover the places you like (and would like to write for) so you can learn their tone, audience and style. Think about them: Which is the audience for each? How does each adapt to its audience? What appeals/repels, and why?

WRITE.

Write about anything you are interested in. Primarily for yourself, but once you’re comfortable, ask a few friends or family for feedback. And anyone can publish to the web quickly and easily using services like Medium, Wordpress, Blogger andYouTube for video self-publishing.

When it comes to writing the only way to get better at it is by writing and reading more and constantly.

Write simply. Assume intelligence but not knowledge, and try not to use jargon. Picture your reader: generally, the level of a bright 12-year old for a national newspaper works well.

Keep to what the reader needs to know and no more. Generally, avoid methodology, complicated statistics or historical detail unless it is crucial to understanding the story - and even then just to the level that a reader would need to grasp the story. Again though, this will vary from audience to audience and publication to publication.

Finally, try to stay neutral and not make your own views known. Use words like “said”, “added”, “continued”, rather than value-laden words like “growled”, “admitted”, “suggested”, etc.

That said, although any science writer tries to be as balanced and unbiased as possible, there is no such thing as unbiased journalism/writing. After all, it is done by humans and, for better or worse, we all carry with us some biases, intentional or not, conscious or unconscious. It is impossible to be completely objective, particularly when many of the outlets we ourselves write for have their own worldview.

As a science writer, your goal is to try to be as rigorous in sticking to the facts and reputable, reliable evidence as possible, while constructing the messages your outlet, story and audience demands.

Although you should be fair and responsible to your sources and the story/facts, as a science writer you are not obligated to defer to science or scientists. As New Scientist says in its pitching guide, “We are on the side of science, not the side of scientists. Our basic duty is to assess the quality of the science — not to act as a mouthpiece for scientists.”

Where do I find story ideas?

A science writer’s bread and butter is to report new results from journals and conferences.

Science – for better or worse – relies on the publishing of research as peer-reviewed scientific papers, and a key part of a science writer’s job is to write about the latest published research. You can find this on the websites of any of the major journals (e.g. Nature, Science, Cell, JAMA) or by searching databases like PubMed or Google Scholar for particular keywords.

A great deal of science journalism and communications comes, again for better or worse, from press releases put out by companies, universities, funders and scientific publishers – the purpose of which is to get publicity for their people, work and company/institution. These are often about the latest published papers, but can also be about the launch of a project or study, or a notable achievement by one of their scientists. You can find these in the media or press releases section of most of these companies' websites. You might also like to look at press release databases from the likes of Alphagalileo, Eurekalert, or sites like Science Daily that publish these general press releases as news stories. There also exist news websites run by individual academic institutions or groups of them such as Futurity.

Some scientists write about their research as it’s ongoing in blogs, on media websites like The Conversation, or on their social media. These can give interesting leads or ideas to things you might like to write about.

There’s nothing wrong with being inspired by things you’ve read elsewhere. Perhaps a news or feature article in a newspaper sparked a different angle or topic? Or there are unanswered questions you might have liked that article to explore?

Ask yourself, "where's the science in this story?".

Likewise, when you see a more general story, ask yourself "is there a science angle?"

What makes a story newsworthy?

This depends on audience and publication (which each have particular needs and interests), but generally a “newsworthy” story is at least one or more of these three:

NEW. It’s (usually very) recently happened, the information is literally ‘new’ to the reader.

RELEVANT. It is about something that affects the reader (e.g. a change in energy prices), or which the reader of that publication is interested in (e.g. a reader of Chemistry World is interested in chemistry). Think in terms of locality, human interest, and topicality.

NOVEL. This can be a factor of ‘newness’, but is also a sense of something unusual or surprising or controversial. A famous phrase is that ‘dog bites man’ is not newsworthy, but ‘man bites dog’ is. Another example of novelty is that something is the first/only/best of something.

There’s a lot of science published and announced every day. But it's not newsworthy if it's incremental, boring, or too specialist, or if the science isn’t up to scratch. When thinking about whether a story is newsworthy, think carefully about the outlet you are writing for and their audience – this will help determine what will be newsworthy to them.

The structure of a news story

News stories are a specific type of writing designed to quickly impart to the reader the top-line facts about something that has recently happened.

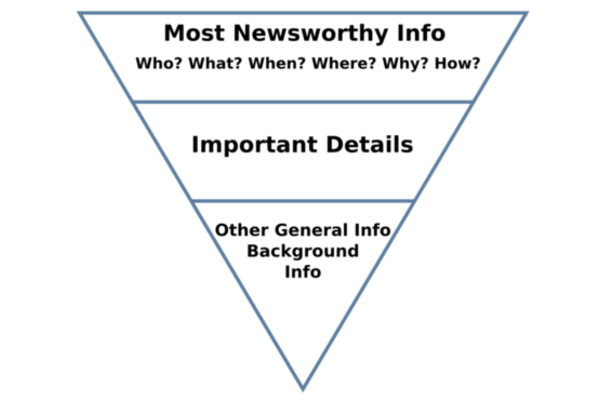

They summarise the story at the beginning into a single line headline (though in major publications this is often written by the sub/copyeditor rather than the journalist) and then a first paragraph covering the “5 Ws” (who, what, when, where, why). It then flows into what’s known as an “inverse pyramid” putting the least important information toward the end.

After the headline and first paragraph, consider including a quote from someone (to help add some human factor), then background. There’s no need to worry too much about an ending in news, it can just stop or tail off.

The inverse pyramid stems from the way newspapers were originally put together – reporters had to read out their copy over phone lines to someone preparing it for the page on the other side. Calls could get cut off, while printers had to literally cut bits off to fit in the space on page. The most important information was given first to accommodate these circumstances, but this has become useful in the modern era. In an age of information overload, many of us tend to skim lots of different stories, whether on page, on a screen or in smartphone notifications or tweets, deciding in a split second what to read and taking away just what we may have bothered to read. Thus, even if your reader doesn’t finish your whole story, they can leave with the gist of what the news is.

How to interview subjects

Preparation is key: do your research on your subject. Prepare questions beforehand but be prepared to deviate according to the answers.

Email is usually best for reaching out to people. It’s generally easy to find the contact email for scientists via Google and other search engines – they are often listed on their university/institution page, or indeed in papers they have written.

Respect your interviewee. Be clear about what information you want, and tell the interviewee in general terms when you make the appointment. Dress properly. Be polite. Be on time (and make sure you know where you are going). Be clear about what you want. Prepare properly. And say thank you at the end!

In terms of questions, think about your readers. What will they want to know?

For most interviews with scientists, you are asking basically two questions: What have you found and what does it mean for me/my family/my community/my country/my planet?

Ask open questions: “Can you tell me about…”, “How did that happen?” rather than questions which can be answered yes or no.

Don’t be afraid to ask seemingly stupid questions. This includes checking spellings of names, dates, affiliations etc.

Listen to the answers. Something they say may lead to an unexpected follow up question.

Probe: think in boxes – e.g., past/present/future; new development/why better than old/future prospects.

Know the views of your interviewee. Put opposing views in the third person: “Some people see this differently. They say that…”, “What would you say to people who argue that…”

Recap – summarise: “So, in broad terms, what you’re saying is…”, “Let me make sure I’ve understood you…”. This might prompt another comment, as well as confirming if you’ve understood correctly.

Don’t leave without all the information you need.

But also don’t be afraid to email or call back to check things or ask follow up questions. Most people are more than happy to help (although note that some, especially higher profile people, may be pressed for time).

Should I record the interview?

Generally, yes. It’s a useful way of listening back to be sure you’ve heard things correctly and to quote accurately. This can be reassuring for the interviewer and aids your understanding. On the other hand, it can be intimidating for some interviewees and listening back or transcribing later is time-consuming.

If you record a call, tell the interviewee you’re doing so at the start. You can say it’s just for your own records and accuracy, but if you intend to use it for audio or video, you must ask their permission.

TEST YOUR SET UP BEFOREHAND - MAKE SURE YOU HAVE ENOUGH BATTERY, STORAGE SPACE ETC.

DOUBLE CHECK IT IS ACTUALLY RECORDING.

You don’t need fancy dictaphones (although there are great specialist ones available, particularly for broadcast quality) – any smartphone voice recorder app, or even the recording function within Zoom, Skype etc. can work. Either record in app or use with a speaker phone (laptop call + smartphone recorder can work).

In-ear mics are also available e.g. this Olympus one.

Playback tip: note most players allow you to playback at double speed, which can save you a LOT of time.

Transcription

This is the bane of any writer’s life but is very useful, especially for going over what was said. There are services that transcribe for you, but it's a luxury and obviously costs money. Automated software is available. Here are a few useful articles exploring this:

- App for journalists: Voice Record Pro, for transcribing audio interviews – Journalism.co.uk

- The best automatic transcription tools for journalists – Poynter

- The Best New Ways to Transcribe. An Overview of 28 Tools for Efficiently… | by Jeremy Caplan | Medium

- Otter.ai is commonly used by many journalists, or the more expensive Trint.

How to pitch ideas to an editor/publication

Pitching is a key part of being a writer/journalist. An editor will receive hundreds of pitches from freelancers and their staff journalists every week and it is their job to sift through and decide which few to commission for the publication. It is your job to make your idea stand out from the crowd so you can actually go ahead and write it.

Think of it like a job interview: you have to sell yourself and your idea. Be clear: Why would this publication do this story? What is the relevance to the publication and audience? What is the takeaway point? Be succinct - think in terms of an elevator pitch/headline/tweet that grabs attention. And ask: Why should they get you to write this and not anyone else?

Common editor pet peeves

- Pitches with no thought at all about the outlet and audience.

- No attempt to see what has previously been written about this before (particularly in the publication in question).

- Topic no story (“I want to write about sleep”. OK, but what exactly about it?)

- Extremely vague pitches.

Tips

- Don’t take it personally if they say no.

- Follow up politely if you don't hear back in a few days but be aware of holidays, weekends and publication deadlines.

- Never pitch to multiple outlets at once - unless you’re sure your angle is different for each. It also limits the exposure of your idea.

- If it’s time sensitive say so - but don’t pressurise.

- Remember: editors are busy people too.

- Make your contacts outside of the pitches - if they have a face to a name they are more likely to at least hear you out.

- Know which section/type of article you are going for in the publication and why.

- Reply promptly.

- Include clips/link to portfolio in your first pitch to a publication/editor. Put your website/social media links in your signature.

- Email or phone? Depends on editor - but generally most editors prefer email. (that said don’t be afraid to follow up by phone if you need to)

- When commissioned: stick to your deadline and wordcount - editors remember who is reliable and easy to work with.

Rate, fees and payment

Always agree this before you start work. Know how much you are willing to work for (and what’s generally reasonable in the market). The journalist Robin Lloyd has put together a document of science outlets you can pitch that has some information about rates.

It’s usually fine to negotiate once the pitch is accepted - the editor should mention fee/rate at this point. Some publications pay flat fees, others a rate by the word (though the latter is rarer in the UK). Bigger brand titles sometimes pay lower - they know you want the recognition and profile boost from the association. Be prepared for this, but don’t sell yourself too short.

Guide navigation

Back to the start

What is science writing?

What do science writers do?

How do I become a science writer?

Getting into specific parts of the media

General tips for getting started (You are here)

Further reading

Courses in science communications

Other organisations similar to ABSW

Credits